Hey! It’s Sheril Mathews from Leading Sapiens. Welcome to my newsletter where I share essential frameworks to help you get smarter at the game of work.

Today we’ll look at metacognition, why it’s important, and resources/strategies to get better at it. This edition is a digest of sorts, where I’ve collected a comprehensive collection of 12 frameworks in one place for ready reference. Each of them is a key piece of the puzzle to help you get better at this essential skill.

What is metacognition

A primary aim in leadership coaching is to develop and hone your metacognition. Why? Because, as you move from an individual contributor to more senior roles, it becomes an increasingly critical factor in your effectiveness and success.

What exactly is it? In Talent is Overrated, What Really Separate World-Class Performers from Everybody Else, Geoff Colvin explains:

The most important self-regulatory skill that top performers use during their work is self-observation. For example, ordinary endurance runners in a race tend to think about anything other than what they’re doing; it’s painful, and they want to take their minds off it. Elite runners, by contrast, focus intensely on themselves; for example, they count their breaths and simultaneously count their strides in order to maintain certain ratios.

Most of us don’t do work with a significant physical element, but the same principle applies in purely mental work. The best performers observe themselves closely. They are in effect able to step outside themselves, monitor what is happening in their own minds, and ask how it’s going. Researchers call this metacognition—knowledge about your own knowledge, thinking about your own thinking. Top performers do this much more systematically than others do; it’s an established part of their routine.

Metacognition is important because situations change as they play out. Apart from its role in finding opportunities for practice, it plays a valuable part in helping top performers adapt to changing conditions.

When a customer raises a completely unexpected problem in a deal negotiation, an excellent businessperson can pause mentally and observe his or her own mental processes as if from outside: Have I fully understood what’s really behind this objection? Am I angry? Am I being hijacked by my emotions? Do I need a different strategy here? What should it be?

In addition, metacognition helps top performers find practice opportunities in evolving situations. Such people can observe their own thinking and ask: What abilities are being taxed in this situation? Can I try out another skill here? Could I be pushing myself a little further? How is it working? Through their ability to observe themselves, they can simultaneously do what they’re doing and practice what they’re doing.

Put simply, metacognition is your ability to think about your thinking. How you view things (you as the observer) influences actions and following results. Metacognition is about observing the observer, and becoming a better observer of ourselves.

What metacognition is:

understanding and controlling our own thinking processes

the mind watching and striving to regulate itself

the process that turns experience into wisdom

awareness of internal emotional states and how it impacts others

skilled self-reflection rather than rumination

feeling and judgment of knowing

understanding the nature and limits of your thinking

Why metacognition is critical

All the below aspects of leadership (and in general your career) benefit/suffer based on how well/under-developed your metacognitive abilities are:

Effective decision-making

Problem-setting/defining (very different from problem-solving)

Managing and interpreting how you’re perceived

Error recognition

Understanding causality

Interpreting problems/situations in multiple ways

Avoiding blindspots that lead to derailment

Understanding your stakeholder’s differing point of view

Navigating organizational politics using different lenses

Your potential action set — limited vs wide-ranging

Given the criticality of metacognition, it’s imperative we work actively to develop this skill. But developing it is not easy because our thinking processes are “automatic, implicit, and abstract”.

12 frameworks for getting better at metacognition

Over the years, I’ve worked with an entire suite of tools/frameworks to help clients with metacognition. Here I’m putting them all in one place.

You can use this edition as a self-coaching manual for getting better at metacognition. I’ve given a small excerpt for each piece. Clicking the links/images will take you to the main article.

How to use them

Before we jump into the frameworks, a caveat: reading on its own will increase awareness but gains won’t be sustained.

Each referenced article is a standalone piece you can spend months on. The trick is in sticking to a process and working at it over time. Work with a coach, mentor, manager, or peer to accelerate this process.

Below are some of the methods (amongst others) I use in coaching engagements:

Self-monitoring and reflection using cues, instructions, and assignments

Thought experiments, scenario planning, creative inventing

Case studies with debriefing and deconstruction

Strategy development processes and exercises

Self-control/regulation exercises

Role playing/role modeling

Reflective journalling

Evaluation exercises

Framing/reframing

Reality testing

Sounds like work? It sure is. But consider the alternative. Will be you be a better thinker/performer 6 months from now vs today? How might that impact your potential opportunities and promotion prospects?

Let’s look at the 12 key pieces of the metacognition puzzle.

(1) Maintaining mental hygiene

There are some common thinking traps known as cognitive distortions that we fall for, especially in stressful situations. This article captures 17 of the most common ones and how to practice awareness.

(2) Problem-setting vs problem-solving

Almost everyone has the term “problem-solving” featured prominently in their resumes. Conversely, barely anyone uses the term “problem-setting”. Except in complex domains like leadership, problem-setting is often more critical than problem-solving. How is it different from problem-solving, and why is it critical to effective leadership?

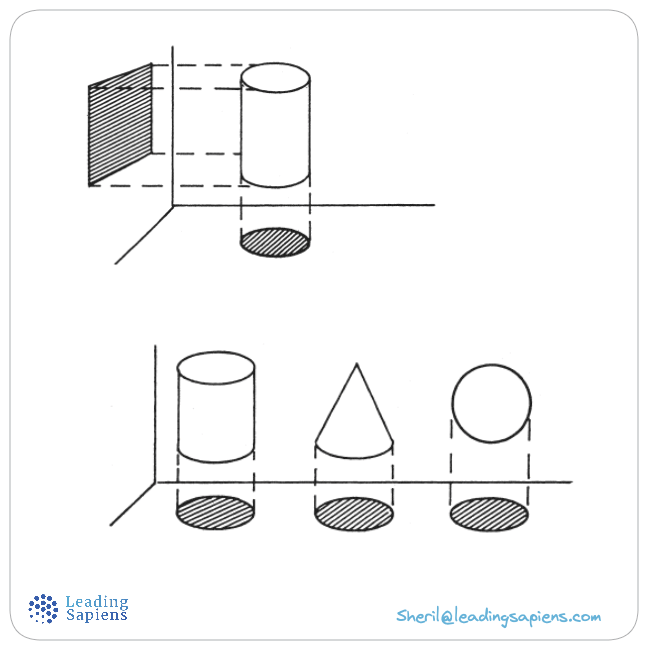

(3) Double and triple-loop learning

The simplest model of performance is that your results follow from your actions. But there are several things leading up to it that influence the whole process. Understanding and mastering the mechanisms of double and triple loop learning is key:

(4) Self-reflection

Reflection is one of the most under-utilized superpowers out there. Here are two pieces to help you understand and get better at it. One delves into why it’s critical, while the other gives you the mechanics of it:

(5) Hidden mental models

Most approaches to mental models are additive: learn this, do that. There’s equal value in identifying and unlearning unhelpful mental models:

(6) Conceptual vs experiential learning

Do you have to read the latest bestseller to become a better leader? How about being a better parent? Most of the time we already know how to, only if we pay attention and trust ourselves. We focus too much on conceptual learning and forget about experiential learning:

(7) Ladder of Inference

How do we go from facts to assumptions to taking action? The ladder of inference shows the mechanics of how we jump to conclusions, and so do others. This is a key tool in learning to communicate and influence.

Here’s a previous newsletter edition that look at the ladder of inference from a different angle.

(8) 4 frames of leadership

Most of us have a fixed way of looking at problems and organizations in general. E.g., some are people-centric while others are more politically oriented. This can be limiting. The Bolman-Deal 4 frames of leadership helps you look at it from multiple angles:

(9) Fallacy of the dominant dimension

Ever wondered why experts often contradict each other? You learn one thing but reality is something else? It’s because all too often they are focusing on one dominant dimension which creates confusion and limits understanding. Viktor Frankl’s framework of dimensional ontology explains this phenomenon:

(10) The Johari Window

Blindspots are a primary reason why careers get derailed. The problem? We simply don’t know what we don’t know. Social norms make this even harder as no one tells us the unvarnished reality. It gets even harder as you move into leadership positions. The Johari Window is a robust tool to elicit critical feedback:

(11) Imposter syndrome and self-doubt

Can doubt be an asset? How about imposter syndrome? I take a closer look at these ever-present aspects of leadership and how you can navigate it:

(12) Context and framing

Leaders have to be masters at framing the context. Here are two deep dives into the basics of context and framing:

That’s a lot of ground we’ve covered. Pick a framework you find interesting and work on it consistently. I can guarantee you’ll see the game differently.

That does it for this edition. If you found this useful, please share so others may benefit. Thanks for reading!