LSW#20 🎭Acting into New Ways of Thinking

Why the verb is easier than the noun

Welcome to edition 20 of the leading sapiens weekly! Today we look at a common, but unhelpful, notion around taking action and changing behavior. If you find value in my writing, consider sharing it with someone who might benefit.

Acting into Thinking vs Thinking into Acting

Consider the following:

Do you wait to be “competent” before acting a certain way?

When trying a new behavior, do you quit because it doesn’t feel “authentic”?

Do you catch yourself saying “I’m just not feeling it today”?

How are you supposed to do that which you don’t “know” yet?

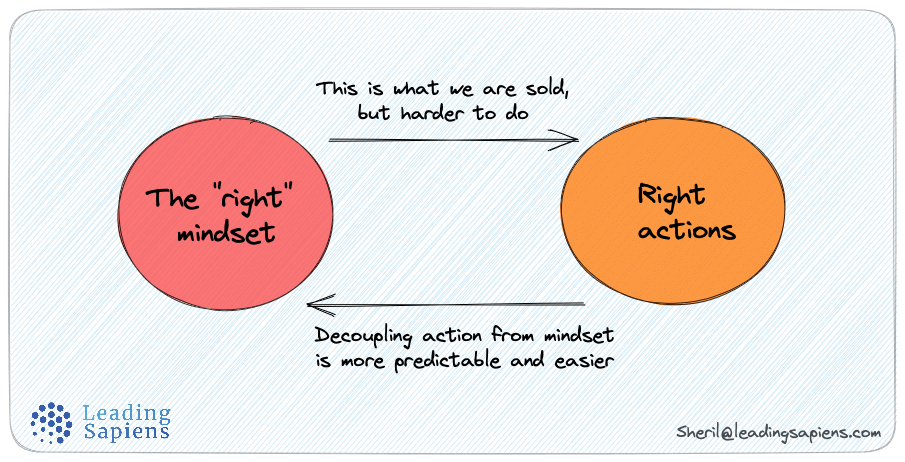

All of the above have a common assumption — that knowing, mindset, or thinking, precedes action, and more importantly that it’s a necessary condition. In fact, it’s not.

In my post Just Do it — Changing Mindset through Action, I highlight how focusing on taking action is often easier than getting into the right “mindset”, the right “feeling state”, or “feeling ready”. Why? Because:

Physical reality is easier to control than psychological reality.

Along the same lines, leading is often easier than leadership. Acting confidently or courageously is easier than “being” confident or courageous.

The mistake is to wait for the noun to materialize —we wait for permission from others, or ourselves, before we act a certain way. The verb tends to be easier than the noun. The verb is often free of judgment and in our control, while the noun is often full of judgement from ourselves and others.

If it is so straightforward why is changing behavior hard?

Two common but mistaken notions trip us up (including and especially yours truly):

That mindset, or thinking, has to change before changing the action or behavior

The new behavior always feels inauthentic at first, so we dismiss it as a lack of skill, or that we are not being our “true selves”

Even the best struggle

I had stumbled upon these concepts from my own hard-won experience with trying different things and failing. It was especially heartening to realize that even folks at the highest levels struggle with the same challenges.

Consider the below experience of London Business School professor Herminia Ibarra. It’s a solid practical demonstration of these simple but powerful ideas.

When I first started teaching MBA students at Harvard, I was a dismal failure. I was young and had no business experience. Although I was a reasonable presenter, I hadn’t yet learned the craft of leading a highly interactive yet structured discussion that ultimately concluded with a set of practical and concrete takeaways. My course ratings were at the bottom of the distribution; I was rapidly losing confidence in my ability to establish my authority in the classroom. I wasn’t credible.

Many senior colleagues tried to help. Most offered well-meaning but relatively useless advice, all a version of this: “You have to be yourself in the classroom.” The problem, however, was that I was being too much myself: too academic, too nervous, too dull, too distant. I invested a lot of time in watching skilled instructors conduct their classes, but everything they did was highly personal: their anecdotes, their life lessons, their jokes, even the ways they walked and talked to create a sense of theater. I wasn’t sure what I could learn from them, and none of it seemed very serious—I wasn’t sure I wanted to teach in the same style they did, either.

One day, a star professor came to watch me teach and offered some advice that I’ll never forget. Now, you need to picture what our teaching amphitheaters look like—a huge, crescent-shaped room with ascending rows, and a pit, with the professor’s desk at the bottom.

The less confident professors, like me, hunched near their desk at the bottom of the pit, close to their notes and far from the students. The experienced teachers marched up and down the aisles, taking up all the space and keeping all ninety of the students on their toes.

My colleague gave me very specific advice:

Your problem is that you think this is all about the content of what you are teaching. That has little to do with it. It ultimately comes down to power and turf. When you walk into this room, you should have one and only one mission: to make it crystal clear to every single one of your students that this is your room and not their room. And there’s only one way you can do that, since they occupy the space all day long for the whole of the year. You have to be a dog and mark your territory in each of the four corners.

Take every single inch of the space. Start with the top, where they think they are safe from your glance. See who is reading theWall Street Journal, who has underlined the case and who has left it blank, what kind of notes they have, and whether those notes have anything to do with the class. Get up close and personal when you talk to them, whisper in their ear, put your arm around them, pat them on their backs. Touch them. Show them that not even the person in the middle seat of the middle row is safe—squirm your way in. While you’re at it, if they’ve got food and you’re hungry, help yourself, take a bite. Then and only then will they know that it’s your room and not their room. Once you’ve got that, you can think about the content that you want them to learn.I was horrified by this advice. I preferred my own ineffective approach by far—spending long nights over-preparing my cases and making sure I knew all the facts and figures so there would be no question I couldn’t answer. But I was desperate enough by then to try it. One day I just started doing what he suggested.

The results were mixed at first. It felt uncomfortable, contrived, contrary to my values as a serious researcher. The students, by and large, didn’t like my getting in their faces. But I began to get more of their attention, and after a while, my new way of behaving in the classroom started to feel like fun. It loosened me up, and I began to know my students better—I learned how they thought about the world and what they wanted to learn.

My objectives for the class shifted from delivering content to orchestrating an impactful learning experience. What I first dismissed as silly theatrics and emotional manipulation, I later came to value as a necessary approach to pedagogy that made the learning stick. I started to see different things in the antics of my more successful colleagues and became more willing to take risks. I stopped worrying about looking foolish. Of course, my learning accelerated. Over time, my ratings improved. I had acted my way into a new way of thinking.

— from Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader by Herminia Ibarra

Leaders Library

Ibarra’s book Act Like a Leader, Think Like a Leader is well worth the read, and chock full of actionable ideas you can implement right away. Her, older book Working Identity is equally good, but focused on career change.

For another helpful angle on the challenges of learning — that you have to do first what you don’t know yet — check out my post: the paradox of real learning.

That's it for this edition. Have a great week!

– Sheril Mathews

Great examples here Sheril. Enjoyed reading this post.

What a great article!